How "Political" Should the Pandemic Be?

This being an election year in the US, the ongoing pandemic is inevitably going to become a major political issue going forward, more retrospectively than prospectively. Prospectively - the US's response going forward from this fall onward, is - for better worse - largely on autopilot or out of the hands of the federal government (e.g., there is not a whole lot the president will be able to do to expedite the development of vaccines). It will be widely believed - indeed already is - that the president (and congress) and the general political characteristics of the US played a major role - either positive or negative - in how well the US responded to the crisis. I think this general belief is false. I was partly motivated to write this after reading a couple pieces in the Atlantic (which I usually have the good sense to avoid), one by Tim Yong expressing, among other things, the belief in the importance of national leadership in responding to the crisis and also at various points suggesting that what administration at the helm makes a big difference, and another criticizing Cass Sunstein's 'technocratic' attitude toward the pandemic while arguing that the crisis can't be depoliticized. It is of course entirely appropriate that Sunstein be criticized for being horribly wrong, but the implication is precisely the opposite of what the article attempted to infer: how things turned out in the US was inevitably going to be almost entirely invariant to politics.

First, even now, it isn't clear what policy response would have minimized the number of deaths from the virus. Broad lockdowns probably reduce the spread significantly, but policymakers in New York have acknowledged that the lockdowns may have also backfired there by inducing people to spend more time confined with elderly or vulnerable relatives with whom they live, and may have increased in intra-household transmission. Tyler Cowen recently quoted on his blog a couple reader comments on this, to the effect that relative sequence of transmission may be very important. In other words, it is important that the most vulnerable get exposed as late as possible relative to the least vulnerable. The emphasis here is on relative sequence. As more 'less vulnerable' people become infected and immune, the rate at which the virus spreads declines, and fewer more vulnerable people get it during the later stages. General lockdowns, the commentor argued, worked in the Spanish flu because that pandemic most aggressively attacked the young rather than the old, and lockdowns reduced the rate of exposure of young, active people relative to older people, while covid19 does the opposite. The implication here is that there is a real possibility that general lockdowns, at least lockdowns not militantly enforced, could backfire. And yet, we can be reasonably certain that modestly enforce lockdowns were going to be the main policy response regardless of who occupied the White House or congress. This is the main tool of public health consensus at this point in the US. Even widespread mask wearing could backfire if it induces more symptomatic people (or infected asymptomatic people) to become more active (in essence, if the Peltzmann effect takes place).

Neither states nor the federal government have the constitutional power or, in all likelihood, political will (or even technical capability and experience) to enforce a strict, draconian lockdown that would be sufficient to stop the virus in its tracks. The most that could be accomplished is slowing the spread. This has already been accomplished to some extent, and probably enough to prevent hospitals from becoming overwhelmed (hospitalization rates are now falling). But spreading out infections over time more than we already have would probably meet diminishing returns, and wouldn't have reduced cumulative fatalities much in the long run. The people saved by 'flattening the curve' are still likely going to get it before a vaccine is available and will not have more effective treatment available. In other words, the US 'flattened the curve' by enough that it probably wouldn't have made much difference had it been flattened still more. I doubt whether another politician at the helm would seriously change how aggressively the US locked down in response to the virus, but even if it would, I seriously doubt it would change it enough to alter the number of people who will have died from the virus even just in this year or two years.

Nor does it seem likely to me that the rate of testing would have been much different under different political leadership or a different political system. The most useful thing that the current administration has done is deregulate private testing, something I would guess if anything is less likely to have occurred under, say, a president Warren (or that international trade in medical supplies would be freer). Existing constraints on prices and payment methods (the irrational unwillingness of bureaucracies to make downpayments to cover fixed costs of manufacturing medical supplies) are unlikely to have been solved by a different regime, especially one with less appreciation for markets. Overall, there seems to be a fairly broad, bipartisan lack of interest in the kinds of policy ideas that would be most helpful right now. Ezra Klein has tried to hoist Elizabeth Warren onto a pedestal here as someone who 'had a plan' relatively early on (back in February, I believe). But realistically, if we are honest to ourselves, her plan would probably have made no difference. The only aspect of her plan was relevant to the pandemic was stockpiling medical supplies, like gloves and masks, and an extra month worth of stockpiling would not have done much to alleviate shortages, not by enough to seriously impact mortality rates. The rest of her plan was just boilerplate political agendas like socializing healthcare (there is not empirical or theoretical reason to believe this would ease the magnitude of the epidemic, most European countries with more socialized healthcare systems are if anything doing worse than the US) and reducing CO2 emissions.

I think there is one set of policies that could have saved us a great deal of trouble, and that is very early widespread testing and tracing. This is something that would have had to start in January and be pursued even more aggressively than in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea to have been effective. This is because three of those places are islands, and one is pretty close to being an island in practice; all of them are also much smaller than the US. It would have been much harder or the US to keep infected travelers out of the country to being with, and to keep infected people within the country from spreading the disease intra-nationally. Beyond the established constitutional and political barriers to more draconian measures that would constrain any regime, the US bureaucracies, at the federal, state, and local level, did not have the relevant experience and institutional flexibility to respond with anywhere near as much effectiveness in this area as the east Asian countries that have responded remotely as well. The US hadn't had as much experience dealing with comparable outbreaks like SARS, MERS, swine flue, etc. as these countries had, nor have such events been scarred into our collective consciousness (or that of other western countries) the way they have in these east Asian countries, which has doubtless affected how the general populace has responded. And note that the lack of preparedness and experience I am describing would not have been mitigated by different leadership: it permeated the relevant institutions from the ground up. It seems clear to me from looking at the responses of countries like Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea that they benefited not merely from better leadership but being more prepared and responsive at the ground level. Officials tasked with executing the response were much more effective than their counterparts in the US likely had any hope of being even if we'd started testing and tracing in January. Finally, once we failed to keep the prevalence of the virus at very low levels (and again, for geographical, demographic, legal, and cultural reasons, I think this would be much harder to do in the US than in Taiwan or South Korea), I think it was pretty much inevitable that the virus would spread thoroughly throughout the country. Again, the spread might have slowed, but ultimately I think the cumulative mortality from the virus a year or two down the road would be similar to what it will be in our current timeline.

The best empirical data we have on variation in mortality rates (I'm using general mortality rate, I should note, because the number of cases isn't particularly informative, as it's mainly just reflective of testing patterns) is in Europe and other developed countries with reliable data. Currently, every large western European country except Germany (The UK, Italy, Spain, and France) has a much higher mortality to population ratio than the US. Western Europe on average seems to be doing significantly worse than the US. I point this out because critics of the current administration from the left mostly seem to believe we should emulate western European countries in our healthcare system (as well as many other ways), and some have gone so far as to argue that if our system were more like the ones in Europe, the pandemic would have been dealt with better. This doesn't not however appear to be the case. I don't know the extent to which preparedness varied by country in Europe, but countries like the UK and Sweden, which have been fairly 'lax' in their response, don't stand out as doing horribly worse. Sweden has had significantly more cases than Denmark and Norway, but the UK has had fewer than France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Of course, there are myriad factors like population density, rate of urbanization, whether or not you're an island, etc. that one would have to control for to get an idea of the relative effectiveness of the policy response of each country, but then dovetails with my central point: the trajectory of the epidemic is mostly determined by factors that are beyond the control of the state and are invariant to politics, even for fairly large variations in policy response. And it is likely that even countries that have handled the crisis fairly well, like Germany, will ultimately merely see their fatalities spread out over a longer period of time rather than reduced in number. This is of course a worthy goal, and I expect mortality rates will probably be lower in countries that don't get as overwhelmed as Italy and Spain, but the US seems to have accomplished as much already, so if the US had managed to spread out the epidemic as effectively as, say, Germany or Canada, seem to be doing at the moment, it isn't clear that this would significantly reduce the total number who die from the virus in the 'longer' run (by which I mean a year or two down the road).

The bottom line: for better or worse, how the US responded to the pandemic was probably more or less invariant to political factors, meaning either the politicians or parties in power or even the most prominent and debated characteristics of the political system. Many believe that the US has responded terribly due to the Trump administration, for example. This is unlikely though; the outcome thus far in the US is middling among western nations (US fatalities per million people is slightly lower than the population-weighted median among western countries, defined as Europe plus anglophone countries in North America and Oceania), and what differentiates the US from the eastern nations that have been more successful are not factors that are 'political,' at least in the sense that policies being argued about would make a significant difference. Moreover, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are probably the three developed countries (well, two countries and one autonomous region) people on the left in the US would like us to emulate least. Indeed, I can't help but mention, given how many on the left and even the right have been arguing that the ongoing crisis is supposed to reflect poorly on libertarianism (or 'neoliberalism'): measured in terms of the size of government and economic freedom, these three countries are among the most economically libertarian countries in the world. It would thus be an uphill battle to argue that the lesson here is that we would've done better if we'd adopted policies similar to France, the UK, or even Germany.

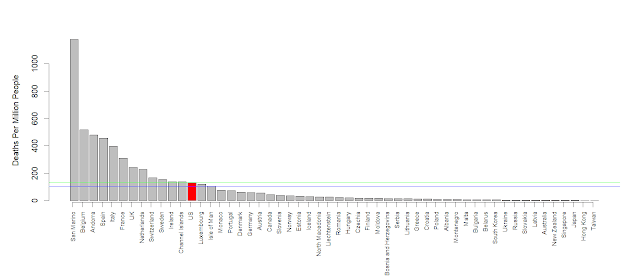

Deaths per million by country among developed countries. The blue horizontal line is the population-weighted median excluding the US, and the green line is population-weighted median among western countries excluding the US.

On the other side, doubtless supporters of the Trump administration will try to argue that, juxtaposing the US with the poorer outcomes in most of Europe, that the administrations response was a relative success. This also seems unlikely to be true. It is not as if the US has done more extensive testing than its European counterparts, nor for the most part has it more aggressively shutdown activities that spread the virus. I think it is true that the US did genuinely respond better in ways that will turn out to have reduced the mortality rate than Italy and Spain, but those are extreme comparisons, and also is unlikely to be due to federal action, and more due to the diffuse responses of states and cities and the general quality of healthcare on the ground in the US. In other words, to the extent that the US outperformed some other developed countries, it was due to far more decentralized factors. It was also probably largely due to luck: Italy was more heavily exposed to the virus much earlier. There are also demographic and cultural reasons why elderly and vulnerable people were probably more exposed in Italy and Spain than elsewhere. As a pseudo-defense of those country's governments, however competently or incompetently we conclude they reacted, there seems to be little they could've done differently to dramatically alter the course of the disease that doesn't fall into the 'hindsight is 20/20' category.

I should note that I am not saying the trajectory of the epidemic in each country is totally invariant to public policy. I am merely saying that the policies that would have made a difference would probably have to have been in place well before the virus hit, and were not (and largely still are not) politically 'on the table.' Moreover, policies related to the standard political issues that dominate popular politics (e.g., healthcare policy) would not have made a difference. It is possible that going forward, policies that might matter for pandemic response will become more relevant, and that constraints on public policy will change in ways that allow for improvements in the response. However, I think that the possibility of that happening is, if anything, severely hampered when people try to argue that had different politicians among our current repertoire been in charge, things would've been seriously better, or worse, than they have been, and disingenuously try to argue that their already favored policies on unrelated issues would have dramatically altered the course of the pandemic. Such contentions are hard to square with the data and run the risk of seriously depleting the quality of public discourse on how to deal with future public health problems. If I am to summarize, it is not so much that I am making a normative claim that we shouldn't politicize the pandemic, but rather that, as a matter of fact, the pandemic is not nearly as political as political commentators are trying to make it (usually for the purpose of turning into a cudgel). Politics, or at least politics as usual, simply wouldn't have saved us.

Comments

Post a Comment